Article

Copper-an essential trace element

Copper is an essential trace element, meaning it is required by animals in very small amounts (mg/d) for normal body functioning.

We often talk about copper as essential for cattle, but potentially toxic for sheep. Here, we will try to ‘unpack’ this somewhat confounding topic, to help you optimise copper supply for stock health and performance.

The importance of copper for ruminants

Copper is essential for the functioning of many different enzymes, including those involved in energy metabolism, connective tissue development, iron transport, coat pigmentation and antioxidant functioning.

| Copper dependant enzyme | Function | Impacts of copper deficiency (enzyme not functioning correctly) |

| Cytochrome oxidase (CCO) | Energy metabolism | Reduced growth, immuno-suppression, nervous tissue degeneration (swayback) |

| Ceruloplasmin (cp) | Copper and iron transport | Anaemia (weakness, poor growth) |

| Superoxidase dismutase (SOD) | Antioxidant | Reduced immunity and fertility (poor conception rates) |

| Tyrosinase | Tyrosine → melanin | Depigmentation (eye spectacles) |

| Lysyl oxidase | Connective tissue development | Connective tissue disorders |

Subclinical (mild/early stage deficiency)

So, what happens when copper is lacking and these enzymes don’t function correctly? The ‘classical’ signs of copper deficiency that we first tend to think of are poor fertility and depigmentation (‘eye spectacles’) in adult animals and poor growth and Swayback in youngstock. However because of the many different functions of copper, signs can be much more varied and may also include:

- Unthriftiness

- Poor appetite

- Increases risk of infections

- Delayed oestrus

- Poor conception rates

- Reduced milk yield

Clinical (severe/late stage deficiency)

- Scours

- Swayback (neonatal ataxia) in lambs

- Lameness and leg weakness

- Anaemia

- Sudden heart failure (falling disease)

- De-pigmentation and loss of hair

The requirement for copper supplementation

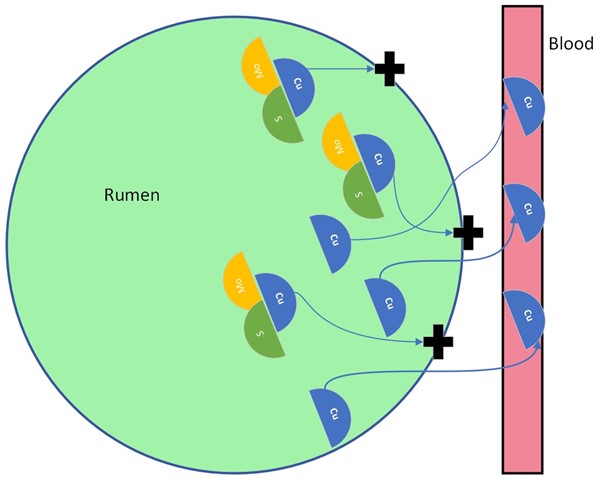

Copper supply in ruminant diets is complicated by the fact that copper is readily ‘locked-up’ in the rumen by molybdenum and sulphur. These three elements react together to form compounds called copper-thiomolybdates which cannot be absorbed. The more molybdenum and sulphur present, the greater the proportion of dietary copper that becomes ‘locked up’, causing what is known as a ‘secondary copper deficiency’.

- Primary deficiency – copper intake does not meet animal requirements

- Secondary deficiency – copper intake is sufficient, but is ‘locked-up’ and not absorbed

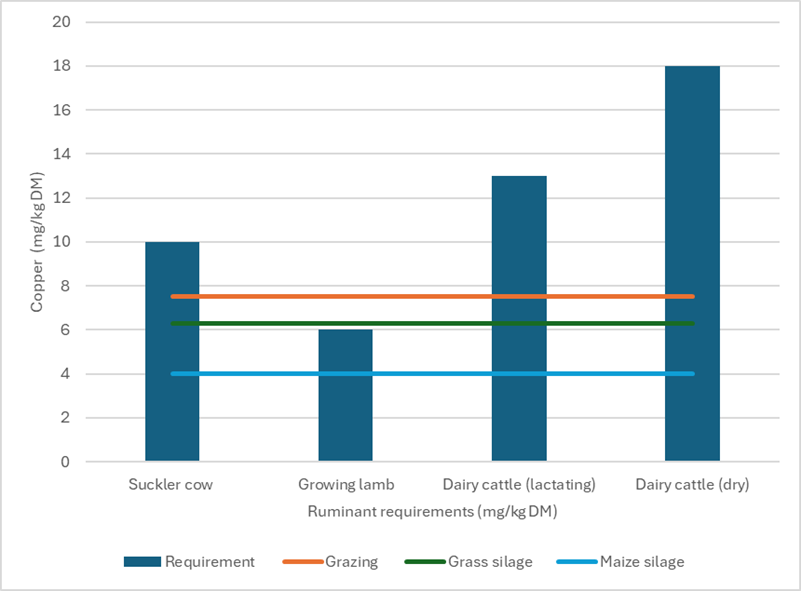

Copper requirements vary depending on species, stage of production and molybdenum/sulphur levels in the diet. Approximate requirements are shown in the table below. Sheep have a lower requirement for copper because they are more susceptible to toxicity, having a very limited capacity to excrete copper. Dry cows have higher copper requirements than lactating animals, this is because the requirement for foetal growth is greater than the requirement for lactation.

| Copper requirement (mg/kg DM) | |

| Ewes | 6-8 |

| Weaned lambs | 6 |

| Suckler cattle | 10 |

| Growing/finishing cattle | 10-12 |

| Dairy (lactating) | 12-14 |

| Dairy (dry cow) | 18 |

Copper levels in UK grazing and forages vary depending on soil type, plant species and stage of maturity (5-8mg/kg DM). Overall levels are usually sufficient to meet requirements for sheep, but short of the requirements for cattle. Maize and whole crop silages contain lower levels of copper (3-5mg/kg DM) as cereals are generally poor sources.

Risks of copper oversupply/toxicity

Whilst essential, excessive copper is toxic to ruminants and in recent years copper toxicity has become problematic in dairy cattle due to oversupplementation. Due to the low levels in forage, ruminants are adapted to store copper in the liver. This means that if supplied in excess for a prolonged period, copper can accumulate to toxic levels in the liver, this process is often ‘silent’ with no obvious clinical signs. Eventually, the liver becomes ‘overloaded’ and the stored copper is released, with death occurring within a few days. This is known as a ‘haemolytic crisis’.

Copper supplementation options

There are several different methods to supply supplemental copper. Due to the risks of oversupply and toxicity, it is important to look at different sources of copper already going into the diet, including forage, compound, protein blends and any supplements, when assessing the requirement for additional supplementation.

Depending on how they are offered, supplements are classified as either ‘direct’ (drenches, bolus) or ‘indirect’ (blocks, buckets, powdered minerals). Direct supplements have the advantage of ensuring that all animals receive the same level of supplementation, however can be time-consuming to administer and more costly than the indirect forms of supplementation. The use of indirect supplements can also be a useful method of providing multiple sources of copper, both organic or rumen-protected, and inorganic (copper salts). This is particularly beneficial for ‘lock-up’ situations, helping to ensure stock absorb enough copper to meet their requirements, without it being ‘locked-up’ by molybdenum and sulphur.

Fantastic information